Please Note: This text and its audio recording contain descriptions of violence and war crimes, as well as an analysis of human behavior relating to sensitive topics, including racism, intolerance, sexual and physical violence, and acts of genocide. Some images might be disturbing to readers. Be mindful of the content before continuing.

Visit Mental Health America’s site for information on mental health, getting help, and taking action.

Introduction

Today’s article is part of a series of blog posts concerning genocide and the ten stages of genocide outlined by Gregory H. Stanton. The purpose is not only to raise awareness of the multiple genocides from the past and the present, but to provide a set of steps within realistic time constraints to promote change, prevention, and tolerance. Each week covers a different stage of genocide, with a specific country or region in focus that has or is experiencing genocide, concluding with an analysis of how that stage is or was evident in the featured genocide and what actions can work against it.

Stage 3, discrimination, is the third stage of genocide. The case study is Afghanistan.

I. Jawahir Sedaqat. Bamyan Valley, Central Afghanistan. January 29, 2021.

The mountainous city of Bamyan — or the “Valley of Gods” — peaks at over 8,000 feet above sea level. The city lies within the larger Bamyan Province, a region divided into eight districts, each composed of various ethnic tribes. The most prominent of these are Hazara, and Bamyan is their capital.

Some refer to Bamyan as the ‘Shining Light; ’ ‘Valley of Gods; ’ ‘Roof of the World; ’ and in a month like January, snowcapped mountains, icy blue lakes, and bitter-cold temperatures serve as a dramatic and unexpected backdrop of otherwise flat bottomlands with lush greenery and clear rivers running through its 30-mile valley.

It is, at first glance, a sort of paradise, bounded by cliffs that hold some of the world’s most ancient histories and artifacts. And since 1998 in particular, bounded too, by violence.

An aerial view of the Bamyan province reveals a hollow opening in the mountain that once housed the Bamyan Buddah — a sixth-century statue carved into the cliff side. For years representing the dominance of Buddhism within the region, discriminatory targeting limited and restricted the Hazara way of life until early 2021, when the Taliban snuck bombs into the side of the cliff.

When the logistics of their plan failed, they launched a rocket instead, obliterating the structure and the hope of peace for many.

It was a similar attack that killed Jawahir Sedaqat’s two sons in November 2020 when the Taliban hid two bombs by the side of a road in the city, killing 14 and injuring 45 others.

Since then, Jawahir, as well as countless other mothers, fathers, brothers, and sisters, made the difficult climb to where a Hazara memorial still stands honoring their lost loved ones atop a nearby mountain. They travel regardless of rain, ice, storms, or heavy winds, their bodies worn and faces sinking and red from the frigid temperatures and icy winds.

Their destination is a memorial of rows of photographs, all Hazara faces — standing, trembling in the wind, crowded at the peak of the frozen mountaintop with graves buried just beneath them.

As a crew attempts to film the hike and conduct an interview with Jawahir, she struggles to hold her composure as she arrives and clings to the grave of her boys — her face pressed against rock, filling with tears and her affection aimless, with nobody to receive it. So she clings to stone.

She describes the chaos of what happened the day her sons both died, though she may never know the specifics. “My youngest answered my call from the hospital,” she says between tears, clutching her hijab in one hand and a photo of her son in the other. “He said his brother was injured and asked me to go to the hospital as soon as I could. When I arrived, the doctors were standing around, and he was dying. I went to find my eldest son, and…and he was dead.”

The attack on Shi’a Muslims in the valley — targeting the Hazara population — is only one of the relentless attacks on Hazara claimed by the Taliban. Between 1997 and 1998, they massacred up to 20,000 Hazara, a staggering loss for the community.

Following the 1998 massacre, the Taliban ordered the bodies to be left in the streets, unburied.

Starving dogs later ate the corpses.

For those still alive in Bamyan and other parts of Hazara-populated land in Afghanistan, the attacks that killed Jawahir’s two boys are as routine as the climb they make in memory every day.

In 2000, the Taliban carried out mass murder, which left 31 Hazara dead.

In 2001, 170 Hazara were killed in a matter of days.

In 2002, the U.N. investigated the discovery of three mass graves in Bamyan.

In 2010, a Taliban attack targeted 9 Hazara who died.

In 2015, beheadings.

In 2016, bombings.

In 2018, school bombings.

In 2019, wedding bombings.

In 2020, a funeral attack.

In 2020, a maternity hospital.

In 2020, another school.

And then, November 2020: the day Jawahir Sedaqat lost her sons.

Her journey to remember, and the journey of the thousands of families trudging through the bitter cold for the same reason, reveal an unknown crisis: In a series of worsening discriminatory practices, and repeated attempts at erasing Hazara from Afghanistan, the Hazara are at risk of annihilation.

Their future can only be hoped and prayed for in solidarity as they memorialize those lost.

As she pulls herself away from the graves, she takes solace only in that the Taliban has not yet destroyed this final place of dignity. Her hands cupped, caressing the photographed faces of her boys one at a time, she whispers, “If only to hold them one last time — to grow just one year older, one day longer, one last night. If only…”

Just one more.

II. Bushra Seddique. Kabul, Afghanistan. August 13, 2022.

“I’m trying to explain to everyone — to tell them by my words — a picture of how life back in Afghanistan was but, I can’t find the right words…When I’m saying it was normal…. we had a home, we had a job, we had plans, we know we had a future.”

Bushra Seddique, an editorial director with The Atlantic, describes in detail her experience escaping Afghanistan soon after the Taliban upended women’s rights. But before the escape, the U.S. withdrawal, and the fall of Kabul, and prior to the terroristic days of Afghanistan returned once more like cancer, Seddique paints a picture for the world that we don’t often see or hear about:

“It was…. normal.”

To have plans, a job, and to know that each day presented individual choices, is the Afghanistan Seddique cannot find the words to describe.

She recalls shopping in crowds, men and women alike; the smiles of shopkeepers, the energy; everyone pursuing careers and passions; eating at favorite cafes and restaurants and enjoying drinks and music with friends and family boisterously and joyfully.

She recalls enjoying pop music and ’80s music.

She portrays a community that is vibrant and quivering with life.

The rush of the cars, the music in the shops, the voices of a people who with every utterance seemed to do so with relief, the “pure language” of the moment — to be free, a woman, and educated — this was life. This was happiness. This was freedom in all that was sublime in a single moment.

On the afternoon of August 13, 2021, Seddique received a call from her brother, his voice shaking.

“The Taliban is in the center of Kabul, Bushra. It is no longer safe. Come home. Come home now.”

Within an hour, the streets emptied. The music was off. The cars vanished. Silence.

Within minutes, the life built for years — decades — was ripped apart from all those who knew to run home, but a particular sting to women. Achievements gone. Your children’s future — gone. Your freedom gone. Music, crowds, smiles, joy — gone.

Taliban was inside the Presidential palace.

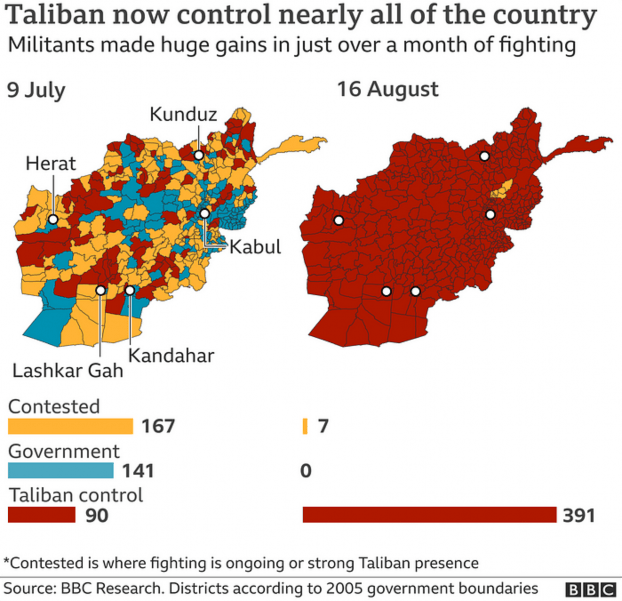

By August 15th, the government had collapsed.

From immediate bans on education for women and girls to the most radical of laws that prevented women from leaving their homes without a husband and prohibitions to work, along with the condoning of gender-based violence, it became evident to Seddique that the language of Afghanistan was no longer pure.

To live in Afghanistan under Taliban rule, For Seddique and all the women and girls across Afghanistan, to live under Taliban rule, the new language was… silence.

A new reality: opportunity did not live here anymore.

III. House Foreign Affairs Committee — Roundtable on Taliban Reprisals. Washington, DC. January 31, 2024. 9:00 a.m.

At the end of the first month of 2024, panelists from multiple organizations appeared in Washington, D.C. for a roundtable hearing before the House Foreign Affairs Committee — organizations such as Moral Compass Federation, No One Left Behind, 1208 Foundation, Operation Recovery, and others. The organizations are almost entirely nonprofit and self-funded.

The hearing is centered on the discussion of support for nationals of Afghanistan who supported U.S. missions there, including sufficient vetting and establishing unique immigrant status for at-risk Afghan allies and relatives of certain members of the Armed Forces so that they can find safe, legal pathways to the U.S. in response to being systematically targeted, hunted, and sought for execution and torture by Taliban forces.

It’s been almost four years since the United States, represented by Zalmay Khalizad, signed the Agreement for Bringing Peace to Afghanistan, known as the US-Taliban deal, resulting in the full withdrawal “of all military forces of the United States” from Afghanistan on February 29, 2020.

On August 15, 2021, as the Taliban took over the country, the world witnessed the reversing of two decades and several billions of dollars’ worth of U.S. assistance on military operations and reconstruction activities in Afghanistan.

Soon after U.S. officials announced the completion of the withdrawal of its military and diplomatic presence, President Biden described the mission as an “extraordinary success.”

Panelists at the HFAC Roundtable on Taliban Reprisals disagree.

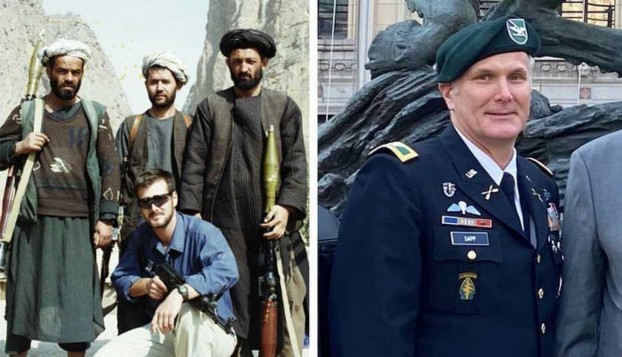

One of them is Colonel Justin Sapp, representing Badger Six, a humanitarian organization aimed at supporting Afghans in need by bringing them to safety.

In his testimony to the committee, Sapp introduces the story of Engineer Mohammed. Sapp begins by stating that what he is about to describe is a “real life account” of what kind of terror our Allies left behind are facing, even years after the withdrawal. Sapp states:

“Engineer is a member of the Hazara ethnic minority, a group that has been the focus of ethnic sectarian persecution for hundreds of years. In 1998, the Taliban killed thousands of Hazara when swaths of Northern Afghanistan fell under their control. These atrocities are driven by profound racial prejudice, and because most Hazara are followers of Shi’a Islam, a religious branch deemed heretical by the Taliban…we put our lives in [Engineer’s] hands. He was indispensable to our team.

Beginning in October 2021, his village was pillaged, and many Hazara homes were razed. The Taliban issued an arrest warrant for Mohammed and detained his family members. While detained, his family members were interrogated and beaten. The Taliban has raided his house 10 times since 2021, stealing property, and, as a final insult, his daughters were threatened with being married off as second and third wives to local Taliban officials.

As of today, Mohammed has been forced to change his location nightly for the past two years.

He has not seen or heard from any of his family since.”

After his testimony, the remaining organizations share stories of similar or worse magnitude. Their testimony illustrates an Afghanistan devoid of identity, Under the Taliban, it is clear that there is no room for Hazara, no future. Similarly, women suffer a fate equivalent to captivity for possibly the rest of their lives. Hazara women, as one might imagine, face the most brutal of trajectories.

A few months before the hearing, aid workers at non-profit organizations in Afghanistan began to speak out after being forced to pay fees and provide services to the Taliban.

In response, in a testimony to the U.S. House Committee on Oversight and Accountability, Inspector General for Afghan Reconstruction John F. Sopko stated the following: “Unfortunately, as I sit here today, I cannot assure this committee or the American taxpayer, we are not currently funding the Taliban. Nor can I assure you that the Taliban are not diverting the money we are sending for the intended recipients.”

IV. Power and Powerlessness

The Hazaras have been systematically targeted and facing discrimination for over 130 years. Women have experienced the most significant discrimination since 1996.

According to Stanton’s The Ten Stages of Genocide document, discrimination is the third stage of genocide, with a much more purposeful and insidious aim of inflicting pain than the initial stages. The official description:

“A dominant group uses law, custom, and political power to deny the rights of other groups. The powerless group may not be given full civil rights or citizenship.”

But in the case of Afghanistan, who is the dominant group? What is meant by dominance? Do we measure dominance by numbers? Or do we measure dominance by power? For all the delusional and self-indulgent arrogance that the Taliban puts on stage, perhaps even the weakest among them is at least somewhat aware that they are disliked on a universal level. How then does a terrorist organization come into dominance?

In Afghanistan, it’s as if it happened overnight.

To understand this, it might be too simplistic to claim democracy alone as the upholder of power falling into the right hands. Indeed, it plays a significant role, but there are, too, societies that are not democratic and do not bomb their ancient world wonders or slit the throats of children. There are democratic nations that have committed genocide. Had establishing democracy been the ultimate solution, Afghanistan wouldn’t have fallen into Taliban hands before many troops were even able to get out.

Of equal importance to comprehending how an unpopular and small number can find their way into a position of power is understanding how the powerless fell to vulnerability. The opposition of these two allows discriminatory practices to become the norm, and practiced long enough, it becomes a societal expectation.

Any solution to this — which provides insight into the bigger picture of discrimination as a part of genocidal processes — requires some historical context and background, both for the Hazara ethnic group and women, and how each faces distinct and mutual widespread discrimination throughout Afghanistan.

Discrimination and Removal of Hazara

For over a century, the Hazaras have suffered countless massacres, genocidal attempts, and egregious human rights violations. Their property has been stolen from them, as evidenced in the example of Engineer by Colonel Justin Sapp at the Roundtable Commission on Taliban Reprisals at the White House.

And there is a reason Engineer was trying so desperately to escape. Since the Taliban takeover in 2021, life has become exponentially more difficult, dangerous, and deadly as Taliban members ramped up a staggering number of suicide bombings at mosques and schools. They used car bombs such as when Jawahhir’s two sons were killed near Bamyan. There is no haven for Hazaras except out.

If we analyze classification, and to an extent symbolization, we can see the ease of discriminating against them. First, they are Shi’a in a predominantly Sunni-practicing country. According to “doctrine,” they are heretics. Put simply, they must be killed for their perceived non-belief.

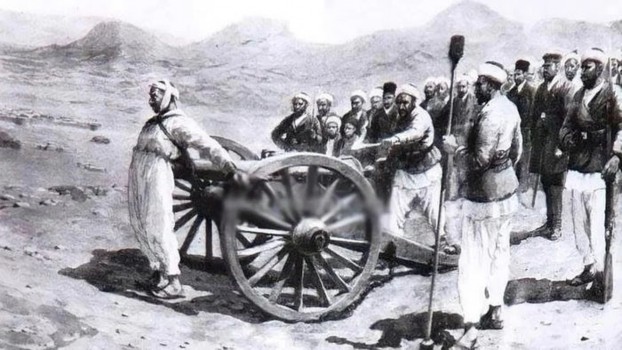

If it seems there are so few of them, it’s because campaigns for hate, enslavement, and genocide have been extremely successful against them. Between 1891 and 1893, the Pashtun tribe, living largely in Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan, were convinced by religious fervor that Hazaras were infidels, resulting in a devastating loss of 60% of the entire Hazara population.

Over the next 12 years, an estimated 400,000 more Hazara families were forcibly and violently displaced. Out of 400 thousand, only 10 percent survived and found safety. Countless tribes within the Hazara community were eliminated. The remaining tribes that did survive lost nearly 90% of their people. It is a loss on a scale of such devastation that it’s almost impossible to comprehend.

In the 1990s, as the Taliban began to issue similar rulings to those seen over 100 years beforehand, a series of discriminatory laws eventually led to the mass murder of Hazaras in two phases, killing roughly 10,000. Later, between 2002–2003, hundreds of violent attacks targeting Hazaras specifically led to thousands more deaths.

And it was discrimination that led them there, which had never stopped since their near elimination in the 1890s. Institutional discrimination took form as Hazara regions within Afghanistan were intentionally left out and neglected to receive vital social services and needed assistance. As a result, development crumbled.

Despite remarkable academic achievements and abilities by Hazaras, they were also vastly underrepresented in any government dealings, including employment. More recently, any Hazaras who were employed as government workers were dismissed. International aid, as we’ve already learned, has been intentionally diverted away from them. After the Taliban takeover, Hazaras are now completely excluded from any government dealings. They have been removed and isolated forcibly from all socio-economic activity.

Discrimination and Disappearance of Women

These intersections of discrimination should sound familiar because Afghan women suffer a similar circumstance.

The return of the Taliban to power in 2021 reignited the worst of fears of a regression in women’s rights, and they worsen with each day. Extreme restrictions such as dress code, lack of education, inability to work, and subservience paint a grim picture of a bleak future. Women have been forced out of public life, including female judges, journalists, and activists, and now live in constant fear for their safety. Meanwhile, gender-based violence remains pervasive, and legal protections for women are often inadequately enforced, if at all. Stoning, hangings, and public shaming are everyday spectacles.

Despite the severe restrictions imposed on them, especially under Taliban rule, they have continued to fight for their rights. Women have organized underground schools, secret networks, and advocacy groups to push back against oppressive norms.

But as their pushback continues, so too does the Taliban’s response, with violence continuing to escalate against them. Public stoning, hangings, beatings, and mass shootings have been reported by countless women who have managed to escape. The reason we lack much testimony beyond escapees is a testament to the severe oppression of women who remain chained in Afghanistan.

With virtually zero participation from women allowed in the workforce, and none allowed within Shariah-enforced governance, extreme hunger, disease, and starvation destroy families who had children before the sudden U.S. withdrawal and Taliban takeover.

Now, they often realize their children are faced with a bleak future, one they never would have wished to bring children into in the first place. Yet they didn’t know, their only “crime” being that of optimism.

The crisis has become so severe with starvation and disease so rampant that some families have reported being forced to sell their children into slavery or forced marriages under Taliban officials, never to see them again, to avoid complete starvation and decimation of the entire family.

VI. Local Action, International Inaction

As the stages of genocide progress, they can seem further out of reach for intervention and prevention. However, if we study those who are suffering, perhaps we can realize the worst targeted, discriminatory practices that are state-legalized in the world, and it is common to realize how many refuse to suffer without complacency.

Women are banned from taking to the streets. They do it anyway. Women are banned from being unaccompanied by a man. They do it anyway. Women are banned from education. They find it anyway. Underground movements in which women dangerously engage in educational practices, practice healthcare they are otherwise banned from and meet privately despite the risks are inspirational, but terrifying.

There are grave and deadly consequences for these actions, but if they can make these incomprehensible sacrifices to stand up for what is right, so can the international community who, for the overwhelming majority, risk little.

One element of genocide that perpetrators count on is passivity. They want not only their targeted victims to be helpless, but bystanders too, including internationally. They are counting on it. Discrimination in Afghanistan is aimed at suffocating women, Hazara, and protesters by any means necessary.

Providing a voice to the voiceless, in this case, could be the only way. It can also mean reflecting on our attitudes at home. We can ask ourselves: How do we perpetuate discriminatory actions instigated by others, whether lawful or not? How do discriminatory attitudes shape our perceptions of the “other” — and where does that justification come from? These questions are a useful starting point to begin looking inward. Until we can challenge discrimination within the relative safety and comfort of our borders, it is less likely we can make a genuine effort to fight discrimination abroad.

That said, discrimination is a crucial stage in the genocidal process for which we can make significant efforts to recognize even more clearly and therefore prevent genocide and crimes against humanity.

To conclude, once we can 1.) look within ourselves from a place of open and honest criticism regarding how we treat the “other,” and 2.) look outward with a renewed sense of empathy and understanding of their suffering. then we can 3.) act and find ways to insert our voices into the places where the Taliban are otherwise intolerant and exfamilies and in doing so, act as the voice for the suffering and voiceless.

The following are specific actions that can be taken on the individual and collective level to fight discrimination at home while opening ourselves to evaluate the importance of equality everywhere, as well as actions to support Afghanistan in the broader and immediate critical sense.

VI. Stage 4: Discrimination. Actions.

Dismantling discrimination begins with the individual. Here are some ideas for recognizing, combatting, and preventing discrimination both locally and abroad.

- Confront Bias: Harvard University offers a free, insightful online course called “Confronting Bias: Thriving Across Our Differences,” available through edX. This, and courses similar to it, can help with understanding implicit bias, and even more importantly: how to counteract it. Another useful course that is shorter is from NonprofitReady.org and can be found here: https://www.nonprofitready.org/unconscious-bias-training

- Identify Unconscious Bias: The Women’s Leadership organization at Stanford University has created a thorough, evidence-based toolkit with specific, actionable steps you can take to identify unconscious bias that can be difficult to detect within ourselves. It’s totally free for download here: https://womensleadership.stanford.edu/resources/tools

- Practice spending in favor of the marginalized: When possible, exercise your economic power for good by choosing to support minority-owned businesses. In the U.S., for example, apps like EatOkra guide you to Black-owned eateries, while websites like WeBuyBlack and Shop Latinx connect consumers to a wide range of products from Black and Latinx entrepreneurs. This helps to direct financial support to marginalized communities who have historically and presently faced waves of discrimination while simultaneously building a habit in the individual of supporting

- Use hashtags and social media: Hashtags can unify voices, so create or follow those that align with anti-discriminatory causes and, of course, hashtags that support genocide prevention and support #FreeAfghanWomen and #StopHazaraGenocide.

Actions for Afghanistan

- Add genocidewatch.com to your Bookmarks and check occasionally for updates on discriminatory practices which may be a sign of genocidal targeting.

- Research and share info on discrimination from platforms like Amnesty International.

- Check out organizations such as Equality Now, which works to end gender-based discrimination globally.

- For men: Explore the resource Engaging Men which contains accessible and digestible information and toolkits/actions that can be taken to end gender-based violence both locally, nationally, and abroad.

- Explore the resource Women for Afghan Women and consider donating, if able. They have an awesome program called Game for Good if you’re a gamer and use Twitch, which is a fun way to show support for and raise funds for women in Afghanistan and refugees.

- Explore the reports and information from the Bamyan Foundation, which keeps an eye on the Hazara living in Bamyan Province and the discriminatory practices they face, plus actions and ways to donate and help.

- Use the hashtag #StopHazaraGenocide and share information you’ve learned about the Hazara population suffering under Taliban rule.

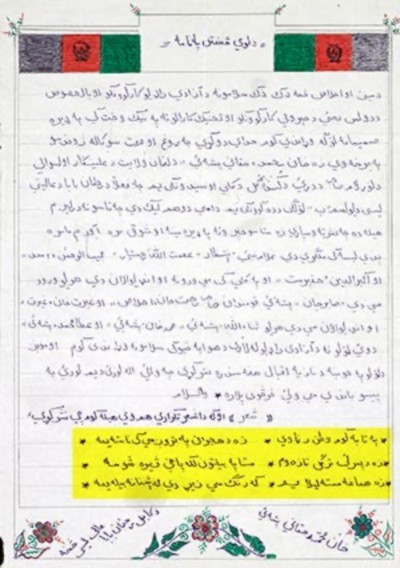

VII. “Voices from Afghanistan” — A Poem from a High School Student. Library of Congress.

“Voices from Afghanistan” is an exhibition curated by the Library of Congress that highlights a glimmer of light not often exposed in Afghanistan or abroad: Radio Azadi, the Afghan branch of Radio Free Europe, and Radio Liberty. Citizens of Afghanistan send letters to the station, which capture both the hardships and the triumphs of life in Afghanistan. It captures their hopes for a better future, for a past we saw in Seddique’s Afghanistan before Afghanistan fell to the Taliban on that fateful day before her escape: hope for the sounds, the movement, the smiles, the smells, and the dreams and fulfillment of those dreams for all. Most of the letters are from Afghan children, otherwise unable to find a way to make sense of the chaos and instability that has become their daily life.

One letter, in the form of a poem, stuck out to me as I explored the exhibition, and I think it’s the best way to end a solemn post like this one, for if a young girl can express hope and strength so beautifully, so can we. Even if we’re told we can’t. We do it anyway. The poem reads:

You give your light to all,

but I suffer away from you

in darkness and separation.

I was fresher than a flower in spring,

but apart from you

in separation,

my color turns yellow

like a leaf in the fall

like a leaf in the fall.

To learn more about the ongoing genocide against Hazara in Afghanistan, discrimination against women, and the ten stages of genocide, visit amnesty.org and genocidewatch.com.

For the next post, we’ll be exploring one of the most insidious of the stage, stage four: dehumanization. The case study is Rwanda.

Until then, join the fight to #StopHazaraGenocide….both in darkness and separation.

Thank you for reading.

Follow the stages at stagesofchange.org.

References

Attewell, W. (2023). The Quiet Violence of Empire: How USAID Waged Counterinsurgency in Afghanistan. University of Minnesota Press.

Country Profile: Afghanistan (Washington, DC). (2008). Library of Congress — Federal Research Division. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g7630.ct003731r/?r=0.277,0.104,0.463,0.365,0

House Foreign Affairs Recorded Stream. (2024). [Recorded Video]. Congress.gov. https://www.congress.gov/committees/video/house-foreign-affairs/hsfa00/lznK1DhShqg

Hozyainova, A. (2014). Sharia and Women’s Rights in Afghanistan (pp. 1–10). United States Institute of Peace.

Information about Bamyan — Bamyan Foundation. (n.d.). Bamyan Foundation. https://bamyanfoundation.org/sister-cities-initiative

Afghan Adjustment Act, no. S.2327, 118th Congress (2023).

Mohammad, N., & Udin, Zack. (2021). Factsheet: Afghanistan. In United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (pp. 1–4). USCIRF. https://www.uscirf.gov/publication/afghanistan-factsheet

Palman, N. (2020). The Hazara Genocide and Systemic Discrimination in Afghanistan. The Leadership Conference On Civil And Human Rights & The Leadership Conference Education Fund. https://civilrights.org/blog/the-hazara-genocide-and-systemic-discrimination-in-afghanistan/

Thomas, C. (2021). U.S. Military Withdrawal and Taliban Takeover in Afghanistan: Frequently Asked Questions (Members and Committees of Congress, District of Columbia). Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/

Voices of the Future — Voices from Afghanistan | Exhibitions — Library of Congress. (n.d.). https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/voices-from-afghanistan/ext/va0036.htmlPalman, N. (2020). The Hazara Genocide and Systemic Discrimination in Afghanistan. The Leadership Conference On Civil And Human Rights & The Leadership Conference Education Fund. https://civilrights.org/blog/the-hazara-genocide-and-systemic-discrimination-in-afghanistan/

Thomas, C. (2021). U.S. Military Withdrawal and Taliban Takeover in Afghanistan: Frequently Asked Questions (Members and Committees of Congress, District of Columbia). Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/

Voices of the Future — Voices from Afghanistan | Exhibitions — Library of Congress. (n.d.). https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/voices-from-afghanistan/ext/va0036.html

Leave a comment